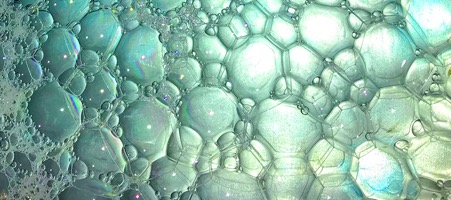

Metaphors are useful ways of understanding complex situations by replacing things with symbols, allowing us to visualize the relationships between them with greater ease. A metaphorical way of thinking about the emergent 21st Century art world is to imagine it as a cluster of bubbles, each one representing small and large creative communities, bumping against each other, sometimes overlapping, sometimes inflating and deflating, occasionally bursting. Constantly dynamic, various bubbles rise and fall as time passes.

A century ago, the art world bubble bath was dominated by a single, large, strong bubble. This avant-garde bubble depended upon the authority of a powerful class of rich Americans to provide support to the modernist project – people like Solomon Guggenheim, Peggy Guggenheim, Abby Rockefeller, Nelson Rockefeller, Edsel Ford, Gertrude Whitney, and John Barnes built a network of foundations providing support for the artists and writers who would become the icons of the avant-garde canon. Through their political influence, they persuaded Franklin Roosevelt to endorse avant-gardism as the aesthetic choice of the state. Through their financial influence, they encouraged a generation of avant-gardists to take positions in America’s burgeoning university system, where they gradually assumed control. They built their own museums which provided cultural centers supporting their ideas. An avant-garde bubble was created that dominated the art world, steered by an oligarchy of American aristocrats who directed aesthetics toward progressive ideology.

In the last quarter of the 20th Century, the avant-garde bubble made by these aristocratic and idealistic avant-gardists was deflated by a new class of wealthy people with a cynical and manipulative view of art as a placeholder for money. These were neither aristocrats nor progressive idealists. They inflated a new capitalist bubble. Andy Warhol led the way, treating art as a product to be exploited in free enterprise. Gallery owners like Saatchi and Gagosian followed, treating their stables of artists like racehorses they could bet on. Later, cynical art flippers like Stefan Simchowitz appeared, discovering young artists who could be manipulated into producing work that he knew he could sell to his wealthy friends. If there was any idealism shared among them, it was the idealism of Gordon Gekko.

Artists realized that they could play the same game. Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst were poster-boys for people hungry to become the new stereotypical capitalist-artist. Recognizing that art could be treated in the same way as pork bellies, Koons became a commodities broker so he could afford to make the things he wanted to make. Hirst financed his art by getting into real estate.

Money provided Koons and Hirst and their imitators with the freedom to make whatever they wanted to regardless of the opinions of second and third generation avant-garde art academics and art critics. By completely ignoring these ideologues Koons and Hirst cast them as ivory tower retirees clinging to memories of their golden days of cultural hegemony and puffing air into their leaking bubble. Koons and Hirst didn’t share their ideas about what true art might be and were busy catering to their own audience, who they understood well.

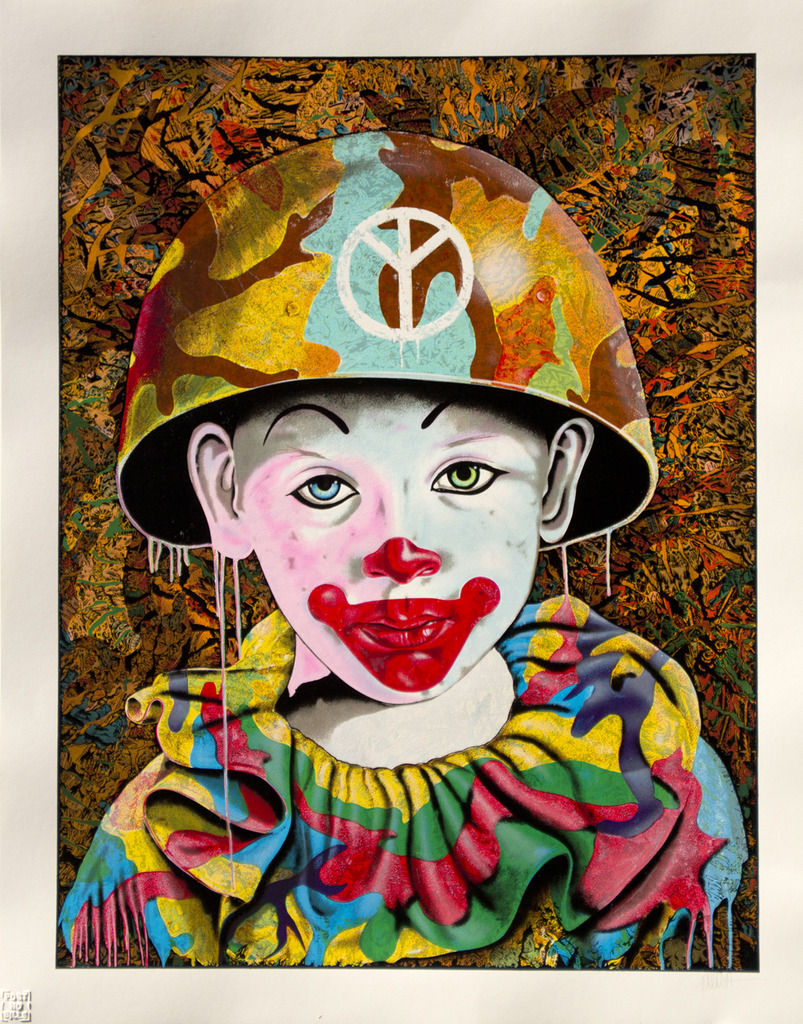

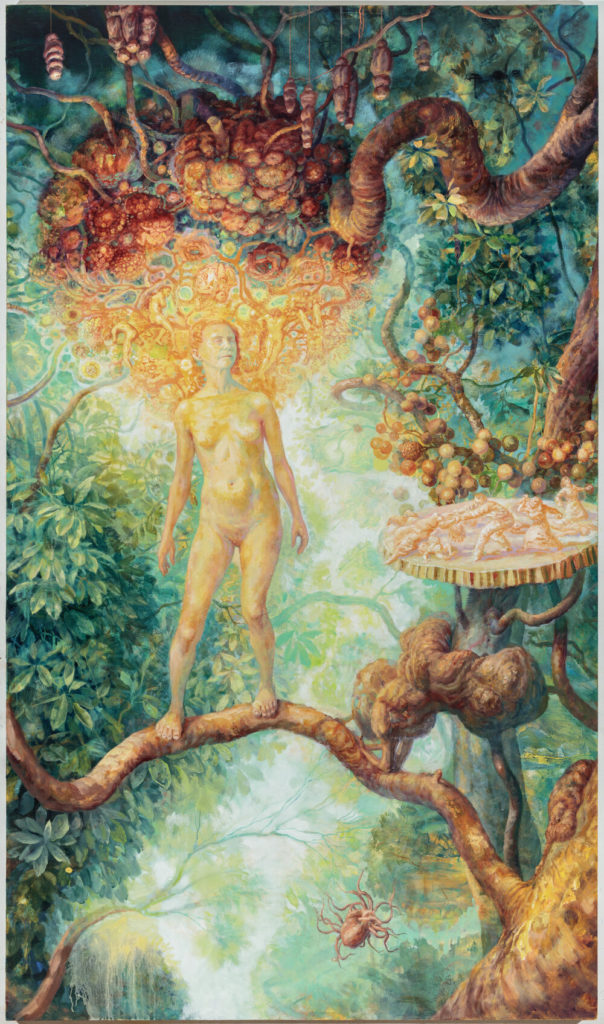

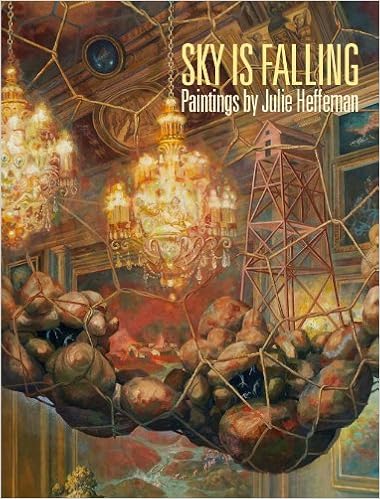

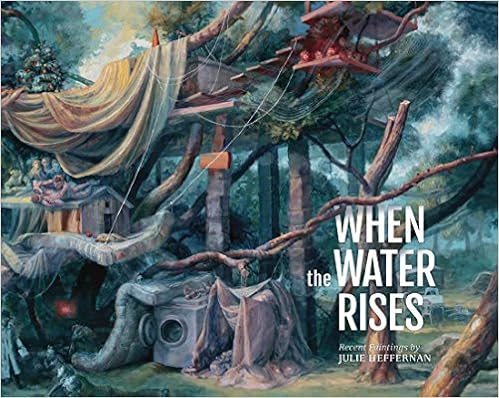

The progressive avant-garde art bubble deflated as the tumescent capitalist art bubble grew. Other bubbles grew too, as various communities found themselves, thanks to the power of social media. In our spectacular society, art is neither merely a tool of the aristocracy nor a vehicle for money. There are many bubbles in the 21st Century art bath. Digital art became tremendously popular and financially successful. Fantasy and Science Fiction art became flourishing bubbles. The ecstatic sculptural art bubble of the Burning Man community thrived. The representational art community bubble grew. The aged avant-garde bubble deflated with a long, slow fart, losing its authority as it diminished. A new bubble of left-wing art activism arose. A nascent bubble of conservative art began to emerge. By the teens several significant art bubbles had manifested as distinctly different parts of the art world. While the capitalist bubble became dominant in high-finance art exchanges and attracted a lot of attention because of the large amounts of money changing hands, other kinds of art produced by and for the other 99% of the population emerged, providing more meaningful experiences. The deflating singular aesthetic bubble of avant-gardism found itself competing with many bubbles of refreshing new art that had no reliance upon the old hierarchy.

In emergent societies art rises up from the people, it isn’t imposed from the top down. The future of emergent art does not lie in the hands of the super wealthy, whose top-down influence is only powerful within the bubble of the people who cater to them. The egalitarian internet allows many millions of people to see sculptures and paintings without the mediation of a monolithic cultural hierarchy of aristocrats, art critics, or experts: this is the bubble-bath of emergence. There is no singular authority. Art bubbles rise and fall as we choose to take interest in them, to participate in them. Small choices may have big impacts. When we like and share images of paintings in our social media, or when we comment in an online conversation, or when we buy paintings or sculptures, we are engaged in inflating an art bubble.