Michael J. Pearce

Kitsch and Emergence – Keynote speech at Paso Robles – May 22nd 2015 – Transcript

When I first began to get serious about art I wanted to paint like Caravaggio but at the art schools I visited I couldn’t find anyone who could teach me how to do so. Instead the professors told me that this was a foolish idea, and that I should give up on representation, which was a dead end. “No-one makes art like that any more.†So to me art was over – I’d missed the boat. I gave up on art schools and got a degree doing theater, came to Los Angeles and worked for a decade as a freelance set designer and thoroughly enjoyed myself, but always felt the tug of painting.

Then in 1996 my friend Christophe Cassidy took me to San Diego to see an exhibit of paintings by Odd Nerdrum. I walked through the show in a daze. A bomb had gone off in my head. These paintings were extraordinary, and they contradicted everything I had been told. Painting was not dead! It was possible to paint like the old masters and make powerful, relevant contemporary works. I couldn’t believe it! I went home and began a search for books on technique. I wanted to paint like Caravaggio again. I found a book by Virgil Elliott that actually described how to paint en grisaille. And I painted as much as I could.

Eventually I became a professor of art and was able to teach classical painting to my students, who are completely unaware of the situation in the 20th Century – they just want to paint and hope to find work in the animation and illustration business, where there is plenty of opportunity for them and employers are hungry for people who have the skills to draw and paint well. This is the most visual culture the world has ever seen – parents, encourage your artist children, send them to a school that will give them traditional training, because if they get traditional training in drawing and painting, they will doubtlessly have happy careers, live long and prosper. Any young artists here can give me a twenty dollar bill afterwards.

I’ve learned that mine was a common experience to many representational artists in the late twentieth century. And this shared experience really bothered me, because I felt as if representational artists were being told we were bad and wrong. Even now the academy treats representational art as an ugly stepdaughter at a family reunion. At the College Art Association meeting in 2012, which was a huge event, with thousands of art professors in attendance, there was not a single paper about any of the representational art that has been made in the past hundred years. This is obviously wrong.

So Mike Adams and I put together The Representational Art Conference because we wanted to bring academic attention to the great representational art that’s being made today. The Representational Art Conference is all about building the community of people who love art that resembles the world we live in, that makes stuff that looks like stuff. We put together the first one in the Fall of 2012. Boy, we were nervous. We carried the weight of a hundred years of denial on our shoulders. But the conference wasn’t just successful as an event, it brought joy to people’s lives.

We were astonished – we got emails from all over the world from people saying that they had been alone, and the conference gave them hope, from people who had felt completely isolated saying that they even though they couldn’t make it to the event, just knowing that it happened gave them faith that their work meant something, and that there is a huge community of people who love representation and have continued making representational art, and that there is a very large market for it. I feel at home within an international community. Many people showing their paintings and sculptures at this festival are part of this community. We are presently looking for funding to continue the conferences into the future. If you are interested in becoming part of this adventure, please contact me. And all the conversations about representational art led me to write down what I think about it and why it’s making a resurgence in the 21st century. I wrote a book, “Art in the Age of Emergenceâ€. You can find it on Amazon, and lots of other online book stores.

What is emergence?

Emergence is the idea that qualities emerge from complex systems that you would not expect. It’s an idea that offers new possibilities for art that haven’t yet been properly thought through, and deserve to be, because emergence helps to give us a better picture of art-making as a whole. I will explain more about emergence soon, but first I want to look at where we are in the academic and big money art word, and how we got there, and why we need to better understand the aesthetics of emergence to move out of the mess we appear to be mired in.

So, today I want to look at why the established academic art world loves stuff like this installation at this years’ Venice Biennale, which is one of dozens of prestigious art fairs held in big cities around the world, but has no tolerance whatsoever for art like this Thomas Kinkade, and why I think that emergence offers a way forward.

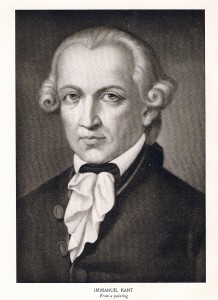

Academic art is doubtlessly the way it is because of theory. I want to look very quickly at three great thinkers whose aesthetics dominate the academy. Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche and Immanuel Kant. Fear nothing – I’m not going to dwell too long on these guys except to show how their ideas dominate the contemporary art world and support the important idea that everything can be art.

First, let’s very quickly have a look at the influence of Karl Marx, whose analysis of class struggle led to communist ideology as a solution to social injustice. I don’t want to dwell long on the problems of Marxism, or its failings in its communist embodiment, other than to note the powerful influence of its ideology in the academic art world in particular. Here’s an installation by Barbara Kruger, known for her anti-capitalist political activism. There is a great deal of art about social justice in museums all over the western world. Here’s a journal dedicated to it, with the Marxist fist signifying solidarity against oppression on the cover. Here’s a sign made by Steve Lambert, who made it to get people “to confront inequality, to confront inequityâ€. He describes it as a trap. Here’s a handbook about art activism.

But Marx’s influence upon art has never been as obvious as it is right now, in Venice, of all places, Venice, the floating city of gilded halls, of merchant success. Right now, Venice is the unlikely host of the most Marxist Biennale ever to have happened. It’s a huge festival of top drawer art that brings the art world glitterati out in force to experience the best of art.

The Biennale rests upon three pillars – described on their website:

• Exhibitions in the National Pavilions, each with its own curator and project

• Collateral Events, approved by the Biennale curator

• An International Exhibition by the Biennale curator, who is chosen specifically for this task

This year the international exhibition was curated by Okwui Enwezor, who called his show “All the World’s Futuresâ€. Here’s what he had to say about his curatorial decisions:

“The 56th International Art Exhibition: All the World’s Futures, will introduce the ARENA, an active space dedicated to continuous live programming across disciplines and located within the Central Pavilion in the Giardini. The linchpin of this program will be the epic live reading of all three volumes of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (Capital). Here, Das Kapital will serve as a kind of Oratorio that will be continuously read live, throughout the exhibition’s seven months’ duration.â€

“Designed by award-winning Ghanaian/British architect David Adjaye, the ARENAwill serve as a gathering-place of the spoken word, the art of the song, recitals, film projections, and a forum for public discussions. Taking the concept of the Sikh event, the Akhand Path (a recitation of the Sikh holy book read continuously over several days by a relay of readers), Das Kapital will be read as a dramatic text by trained actors, directed by artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien, during the entire duration of this years Art Biennale.â€

So here is Marx, read as a holy book for a continual seven month long event, at one of the most important art festivals in the world. And of course all the artists in “All the World’s Futures†are chosen for their Marxist political activism. Which is ironic, because this is an event that celebrates the 1% of the world who can afford to spend millions of dollars on art that frequently offers a message of social justice that would seek to overthrow them. Weird, huh? Some would say it’s hypocritical. Marx’s influence on contemporary art runs pretty deep. I’m not aware of any 21st century art that pushes a conservative political agenda as consciously and publicly as this. I wonder if anyone will ever hold staged readings of Edmund Burke. Perhaps that’s an open niche market.

And if Marx gives us a political underpinning to postmodern art, Nietzsche gives us another of its key themes, that deconstruction may lead to beauty. Nietzsche’s nihilistic advice was clear and serves as a foundation for the destructive impulses of post-modernist adherents:

“That immense framework and planking of concepts to which the needy man clings his whole life long in order to preserve himself is nothing but a scaffolding and toy for the most audacious feats of the liberated intellect. And when it smashes this framework to pieces, throws it into confusion, and puts it back together in an ironic fashion, pairing the most alien things and separating the closest, it is demonstrating that it has no need of these makeshifts of indigence and that it will now be guided by intuitions rather than by concepts. There is no regular path which leads from these intuitions into the land of ghostly schemata, the land of abstractions. There exists no word for these intuitions; when man sees them he grows dumb, or else he speaks only in forbidden metaphors and in unheard-of combinations of concepts. He does this so that by shattering and mocking the old conceptual barriers he may at least correspond creatively to the impression of the powerful present intuition.â€

But where are these “audacious feats of liberated intellectâ€, achieved by liberating the mind from the pernicious effects of its natural evolution? What are their achievements? Is the brokenness of punk the best offer of the postmodernists against the stimulation of the renaissance? Does Dada truly offer a sustainable intellectual challenge for the evolving mind? Such are the nihilistic responses to Nietzsche’s seductive advice, which is a call to destroy and shatter the foundations of human consciousness, where the mind is founded on the formation of concepts. And destruction is seductive because we rebel against restriction, but we cannot gain liberation by destroying our collective cultural consciousness, which transcends any personal frustration, surpasses contemporary political ideology and exceeds the boundaries of states.

Postmodernists in search of Nietzsche’s misguided liberation end in self-indulgence, because humanity does not share their individualistic nihilism. Humans are essentially co-operative, very slowly building collective cultures founded on shared expressions of mind. Instead of constructive progress toward art as a thriving part of culture, Nietzsche gives us the strong theme of brokenness.

Some will say that the Nietzschean cut and paste efforts of post-modern artists or the random drops, scrapes and pours of abstract expressionists are examples of creativity, and this is true at a very basic level, insofar as all acts of manipulating material are solutions to problems of expression of consciousness. Artistic creativity thrives when artists pursue a solution to a problem. Nietzsche’s advocacy of destruction in order to find primitive creativity as a solution to a creative problem is fundamentally opposed to the gradual building of an evolutionary mind, being a retreat to child-like art that can only offer emergent experiences that will fulfill simple generalizations.

Yes – children make spontaneous works of art. Yes, child-like creativity is wonderful. But creativity is only a part of the whole domain of making a work of art. Adults are not children. Adult minds are far more evolved and sophisticated than those of children, that’s why we adults are the parents. Our embrace of Nietzsche’s deconstruction leads us to “anything and everything is art†and leaves us hungry for more sophisticated, more mature expressions of creativity. In art following Nietzsche has resulted in post-modern relativism, in which all things are equal in art. I see relativism as the walking corpse of nihilism wearing a pretty summer dress.

And alongside Marx’s politics and Nietzsche’s relativism, Immanuel Kant said that experiences of beauty are judged, and can only be experienced through “disinterested interestâ€. What he means by that is that we can only make a judgment of whether or not something is beautiful or not by approaching it intellectually – by considering its merits. His influence has made it possible for artists to take anything and offer it up in gallery spaces for the appreciation of its aesthetic merits alone. This is why Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain†has been the center of discussion for a century, making it the most interesting toilet in the history of the world.

Because anything can be art if the aesthetic is disinterested then naturally artists experiment with the boundaries – If a toilet can be art, can a giant butt plug be art? Yes it can. This is an inflatable sculpture by Paul McCarthy. Can a can of artist’s shit be art? Why, yes, it can. Can a machine that manufactures poo be art? Of course it can. Perhaps you’ll notice a theme developing. All of these things have been in art galleries. I hope I didn’t spoil your dinner. The French didn’t think much of the giant butt plug. Someone beat up the artist, and cut holes in the inflatable and deflated it. The obvious problem with Kant’s disinterested interest is that if anything can be art, then nothing is art.

To Kant, pleasure comes as a result of aesthetic judgment. To Kant we are pleased by an image because it satisfies us intellectually. But here’s the problem with Kant. When I put this image on the screen (a mother with a laughing baby) don’t you immediately think of your own experience when your children were born, recalling the love you feel for your children, your hopes for them, your fear of the danger they might face – didn’t you want to protect them in their vulnerability?

Did you really make an intellectual assessment of this picture first? Did you consider the shape, arrangement, rhythm of the image, or did you immediately made sentimental associations with the birth of your own children? Of course the photo immediately puts any parent back into the moment of birth and any aspiring parent forward into the anticipated future. We follow that pleasure with aesthetic judgment, but the sentimental response comes first. When you enjoyed the sentimental experience that the image brought to mind, you were experiencing a kitsch moment. Was it unpleasant? Of course not. We find pleasure in sentiment. We thrive on it. And when we look at art that captures moments that resonate with us we love it and hold those works of art closely to our hearts.

What is kitsch? (Photo of kitsch puppy ornament) It’s more than this, more than cheap tchotchke ornaments. Unlike the Kantian art we saw earlier Milan Kundera once described kitsch as a state of “shitlessnessâ€. To Kundera kitsch describes a world in which the bad stuff doesn’t happen, where everything is good. But kitsch is more than this– we also find kitsch imagery of tough times alongside the idealization – for example the tearful child (photo) , the tragedy of war (photo), the death of a child (photo) – what really distinguishes kitsch pictures and sculptures is that they offer imagery of a world in which emotional responses are sincerely felt. Kitsch images invite and describe emotional experiences. These are images in which we can empathize with others in moments of emotional intensity – the suffering of the dying and those who are left behind; the full dramatic potential of a new child; the sadness of a child who first becomes aware of the transience of beauty, or the immanence of death. Kitsch artists are wholehearted in their appeal to share in the sentimental response to their work. Sentimental pleasure is fundamental to kitsch.

But Kant says that aesthetic judgments must be separate from pleasure, and that aesthetic judgments must be separate from concepts of the good – and so his followers encourage art that deliberately excludes sentiment – there is no greater evil in contemporary art than kitsch. Whenever sentiment appears in contemporary art it must be treated with ironic detachment and blocked from its connection to the mind of the viewer. This is why contemporary art appears to wallow in negativity, because you can’t view a work with disinterest if you are preoccupied by your emotional engagement in it. Contemporary art has said no to emotional appeal. Art without disinterested judgment must be bad because it corrupts the pure aesthetic experience.

And throughout the 20th century we find intellectuals working with the anti-kitsch theme. In his influential essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” the young Marxist Clement Greenberg described kitsch as a corrosive force that would destroy culture. The German writer Hermann Broch had witnessed the Nazis’ manipulation of the German population by the skillful use of sentiment in posters, parades and film and was moved to describe it as “the evil in art” in his essay “Evil in the Value-system of Art”. In Milan Kundera’s “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, set against the backdrop of Communist Prague, kitsch is described as the lie that the world might be better than it actually is. To Adorno it is “poison”. These writers laid the foundations for a post-war repugnance for kitsch that has lingered into our 21st century. Kitsch is still a pejorative word. But all the emotional responses inspired by kitsch – which dwells in sentiment, love, beauty and nostalgia – are normal, healthy human reactions to our experience of life. We all enjoy them and find comfort in them; a life lived without them would be cold and heartless.

But Kundera’s association of kitsch with the evils of the Nazis is superficial, for we see equal use of sentiment in the propaganda of the left – the imagery is so similar that it’s hard to tell which political ideology is which. Here are communist and fascist images of heroic workers from the twentieth century. These images are used to inspire solidarity. But Kitsch itself isn’t evil – like everything else, it can be used for evil, but that doesn’t mean it is evil in itself. Are farmers evil because totalitarian governments used them for their propaganda? Of course not. Using propaganda for despicable ends is evil.

And although we’ve tried to separate emotion from art for a hundred years, disinterested interest is a completely artificial imposition upon the way mind works. The emergent mind is founded upon sensory experience. If art reflects mind, then why would we attempt to deny the value and importance of sentiment in our art? The idea that we could detach ourselves from emotion dehumanizes us as badly as ever. To pretend that human beings can be detached from emotional responses like this is ridiculous. Sentiment is inescapably part of human experience.

We surround ourselves with sentiment – even when we think we do not. In our houses we gather things together as extensions of our selves – pictures of family that bring us nostalgic moments of pleasure as we recall family members, furniture that satisfies our ideals about who we wish to be, kitchen appliances so we can create meals that we share with friends and family, building a shared history with them. We decorate the walls with art that reminds us of our engagement in culture – and if it’s original art it reminds and our friends of our role as a participant in building that culture. If it’s a copy we possess it as a marker of our desire for the original work of art. A house is a box for making a home in. A home is an extension of desire. What could be more kitsch than making a home, a nest for ourselves that comforts us in our experience of the world? Sentiment and kitsch are indivisible. Without sentiment we live in a world without healthy human relationships.

As individuals living within the postmodern society of the spectacle – in a culture dominated by Kant, Nietzsche and Marx, we find ourselves isolated in a world of strangers, who may look like us, but share no empathy with us – although we live in an ever-growing population we are alienated in a world without human sentiment and we fear becoming anonymous. We take endless selfies in an effort to assert individuality and reach out to others via social media, in a desperate search for human contact.

And I think this is why zombies are so popular right now – they perfectly mirror the postmodern world. In zombie movies and tv shows the zombie plague has transformed our population – zombies have no individuality to define one walking corpse from another. They lose their free will, becoming dominated by one simple urge: to consume others, who then become just like the rest of the mass of zombies overrunning the earth. Being undead, zombies lack sentiment; experience no empathy for others; have no regard for human culture, being driven only by their basic instinct to destroy.

But zombies are incapable of self-improvement, being destined to live at base levels where everything is relative. They have no choice but to live as beasts, unconscious of the survivors’ evolving minds. A zombie heart may beat a rhythm of false, dead blood through the walking corpse, but that heart cannot feel love.

The annihilation of the self is a symptom of the postmodern zombie plague, but among the survivors, love is the bridge that lets one mind reach out to touch another and reaffirms the individual as part of the community of survivors. Sentiment saves humanity from the zombies.

Prince Charles is not a zombie. He’s the heir to the throne of England. More interestingly in the context of this lecture he’s a property developer in Cornwall. But if that makes you think that he’s found a nice corner lot for a strip mall with a 7-11 and a Laundromat, think again, because Charles is thinking differently. He’s built an entire town. – I’ll get back to this in a minute. He’s a small part of the way out of zombieland.

Emergence accurately explains a lot about culture, and it gives me cause for optimism because it presents aesthetics that have room for empathy and sentiment.

What is emergence?

Emergence is the idea that there are qualities that are greater than the sum of their parts – like the wetness of water. When we look at water to try to understand it we might reduce it to oxygen and hydrogen, and congratulate ourselves that we understand its structure, but this reduction would not offer us any understanding of the slippery, fluid wetness of water. Reduction looks inward and down into the component parts of complex structure. But reduction misses looking at the qualities of the whole. Wetness is an emergent quality of water, only reached by looking upward and outward.

Another example of emergence is to watch the murmuration of starlings. You wouldn’t predict the motion of the flock by examining an individual starling – the murmuration is an emergent quality of the complex flock itself.

And there are many other emergent qualities, but of particular importance to us is the emergent quality of mind. What is mind? It’s difficult to pin down, isn’t it? I’m proposing that mind is an emergent quality of physiology – that it is the result of the complex systems of the human body.

We know mind evolves during our lifetime, as we grow older our minds develop, we become more sophisticated in our thinking. Nietzsche was absolutely right in his description of the way mind evolves – do you remember his words? He describes the mind as an “immense framework and planking of concepts†but his idea that we should break down the concepts we slowly build as our minds evolve suggests that we can somehow dispose of that framework and do without it. A building with no framework falls down. This is an impossible appeal to mindlessness. What we actually do when building mind is to continually adjust concepts and find new ideas that move us forward, completing and modifying our past ideas. Mind is in constant evolution within the physiology of the human body, with all the sensory experiences and emotions that go with being human.

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy that deals with the study of outward appearance, the study of art, and the nature of beauty. In order to come up with ideas about how we understand art, we must always begin with understanding mind. When our understanding of mind changes, our aesthetics also change. Marx, Kant and Nietzsche dominated twentieth century art because their brilliant analyses of what art might be ran parallel to new discoveries in science and philosophy, and caught the imagination of a population hungry for change, desperate to re-invent culture from the ruins of world war two. But if Marx, Kant and Nietzsche are now inadequate because they fail to account for emergence, and if neuroscience is making new discoveries about how mind works that support emergence, then the aesthetics for the 21st Century must be founded in emergence, must incorporate our new understanding of mind. And with this new aesthetics comes a new openness for sentiment, kitsch and with it, representation.

So I want to go back to this little fellow (picture of a tchotchke puppy ornament), not as an example of the best of what emergence has to offer, but to show how kitsch is foundational to some really sophisticated art that is quite different to that which rises from Kant, Hegel and Nietzsche.

So here are some examples of how these themes appear in material culture, in a sort of hierarchy of kitsch sophistication.

Here’s one of Jeff Koons’ balloon dogs, which amuses countless people who love it for it’s Christmas tree ornament, childish fun – it’s surprising, fresh, and cheerful. What could be more kitsch than a giant balloon dog christmas tree ornament? It’s not terribly sophisticated, but perhaps it raises questions about superficiality and pleasure. Here’s one of John Currin’s paintings – it’s sexy, really well painted, bright and cheerful – totally kitsch. Perhaps it makes us think about the role of women in postmodern culture. Here’s Adrienne Stein’s “La Fête Sauvage†which just won the ARC purchase prize – it’s about as kitsch as can be, and seductive, but loaded with symbolic meaning, the fruit is rotting, the meat is raw. On a more serious note here’s Graydon Parrish’s painting about 9-11. The kitsch themes are still here – the painting describes a moment of suffering, there are young maidens weeping, children with toys, flowers, the old man, the pathos of tragedy, but it’s powerful and symbolic, loaded with allegorical meaning. And here’s a magnificently kitsch ship of fools painted by Carl Dobsky – it’s allegorical and offers a valuable lesson to those who care to think about it.

The characteristic of these works is that they are open, they are made for us, not as an act of self-indulgence. Emergence depends upon co-operation between minds, upon shared experiences, upon looking forward and outward, not inward and down.

I promised you I’d get back to Prince Charles. Here’s his new town, which is called Poundbury. The town is built using architecture that is designed for the people who live there, following the patterns of old English towns, with town squares, pleasant buildings that don’t dominate their surrounding, but harmonize with it. The architects left their egos behind when they designed this place. The town is built for the community, not to satisfy an individual’s hunger for glory.

These works of art and architecture are inspired by our shared experience, and attempt to make sense of it, unlike the art founded upon Kant, Marx and Nietzsche, which attempts to make less sense of it, to break down our efforts to comprehend what is happening to us as we live.

And now, as we return to our homes, I hope you will think about what a difference emergence makes to the alienation of our lives. Look at the things in your homes with a fresh eye for sentiment. And when you think about the art you own and the things you have collected, I hope you will remember these questions: What is a work of art but one mind reaching out to touch another? We have a word for that, don’t we? We call it love. What does the art you own say to you? Does it offer a message based on love? Of shared experience?

Hey

I have a question, i see a lot of items in this shop, I have made a screenshot of some products, https://screenshot.photos/cheaperclothes that you also sell in your shop. But there items are 40% cheaper, well my question is what is the difference between your store, is it the quality or something else, I hope you can answer my question.

Yours truly

Genevieve Calkins

“Sent from my AndroidPhone”

karen viggers bibliographie

alain sagne

editions trabucaire

le rouge vif de la rhubarbe audur ava olafsdottir

olivier richou

jean baptiste legavre